Recover

It started with a print

01 August 2019

With crime rates rising and the number of solved crimes at an all-time low – a chance discovery in the chemistry labs at Loughborough is providing the answer for successfully solving more crime.

A bleak outlook

During the first half of 2019 the media painted a bleak picture in relation to crime levels. On almost a weekly basis we’ve been hit by reports of ‘blood baths’ and ‘violence epidemics’ in the capital and beyond.

Official figures released by the Office for National Statistics* sadly supported this gloomy outlook showing that overall recorded crime in England and Wales rose by 8% to 5.9 million in the year to March 2019, including increases in knife crime, robbery, firearms and public order offences.

These figures also showed that the number of crimes being solved had fallen to an all-time low, with fewer than 1 in 12 offences resulting in a charge or summons. Within this proportion of offences, the number of offences closed as a result of ‘evidential difficulties’ increased from 29% to 32%.

* The figures, which were released in July by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and show the 12 months to March 2019. These figures do not include Greater Manchester Police, one of the biggest police forces in the UK, which records data differently.

A chance discovery

So, what can be done to improve the chances of a crime being solved?

Forensic techniques, including the analysis of fingerprints, play a major role in crime investigations - confirming or disproving an individual’s identity. But what if the evidence is wiped away or destroyed to prevent an individual being identified?

A serendipitous discovery in the chemistry laboratories at Loughborough University holds the answer.

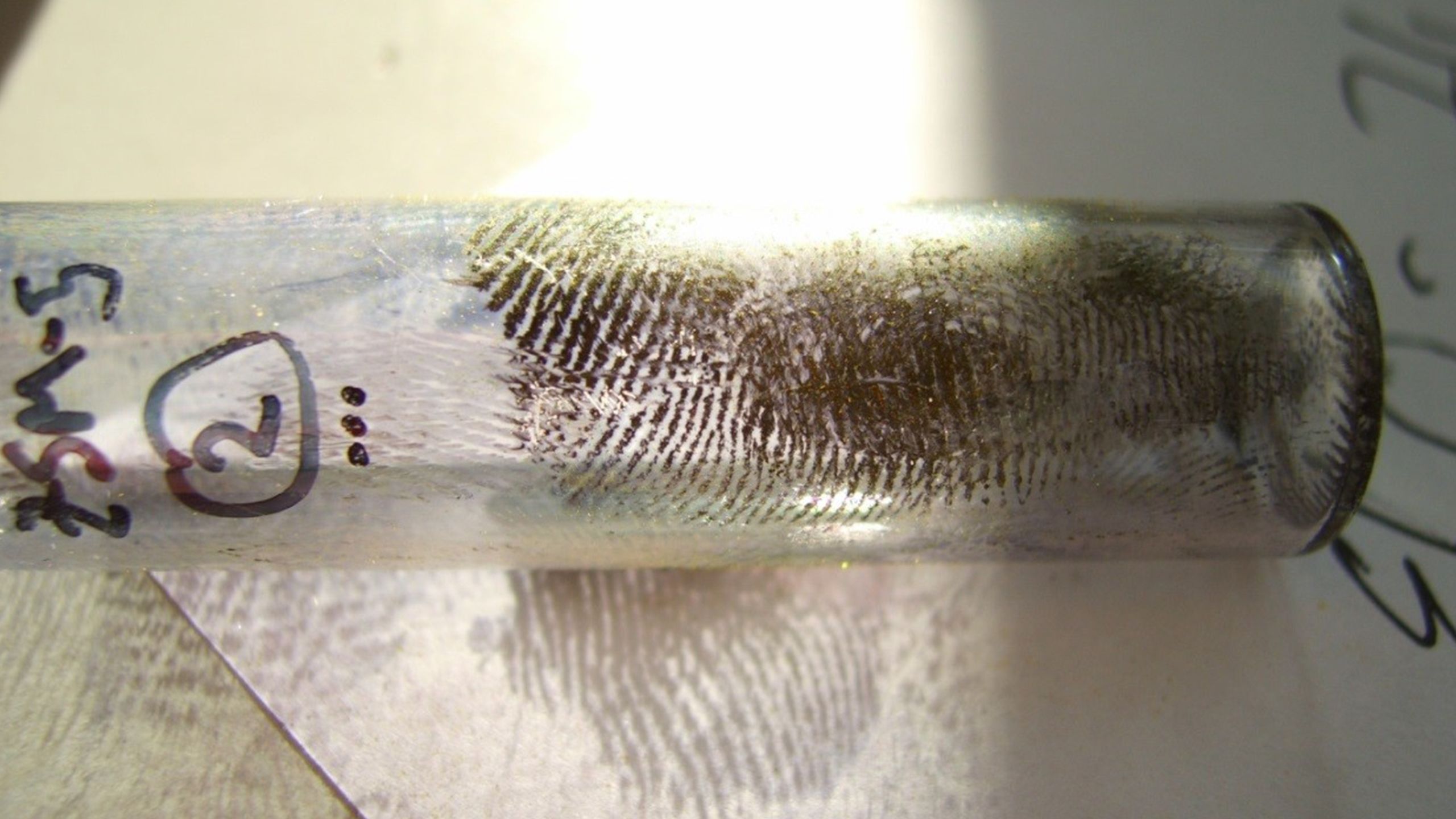

Back in 2008 a team of Loughborough’s inorganic chemists – including (then, PhD student) Dr Roberto King and led by Dr Paul Kelly – noticed that fingerprints were developing on glassware after being exposed to the fumes created by the process they were running.

Although they didn’t possess a forensic background – they knew it was a significant discovery and published their findings in a paper which attracted the attention of Dr Steve Bleay, Senior Forensic Scientist at the Centre for Applied Science and Technology (CAST – now part of the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, DSTL).

From this RECOVER was born.

What is RECOVER?

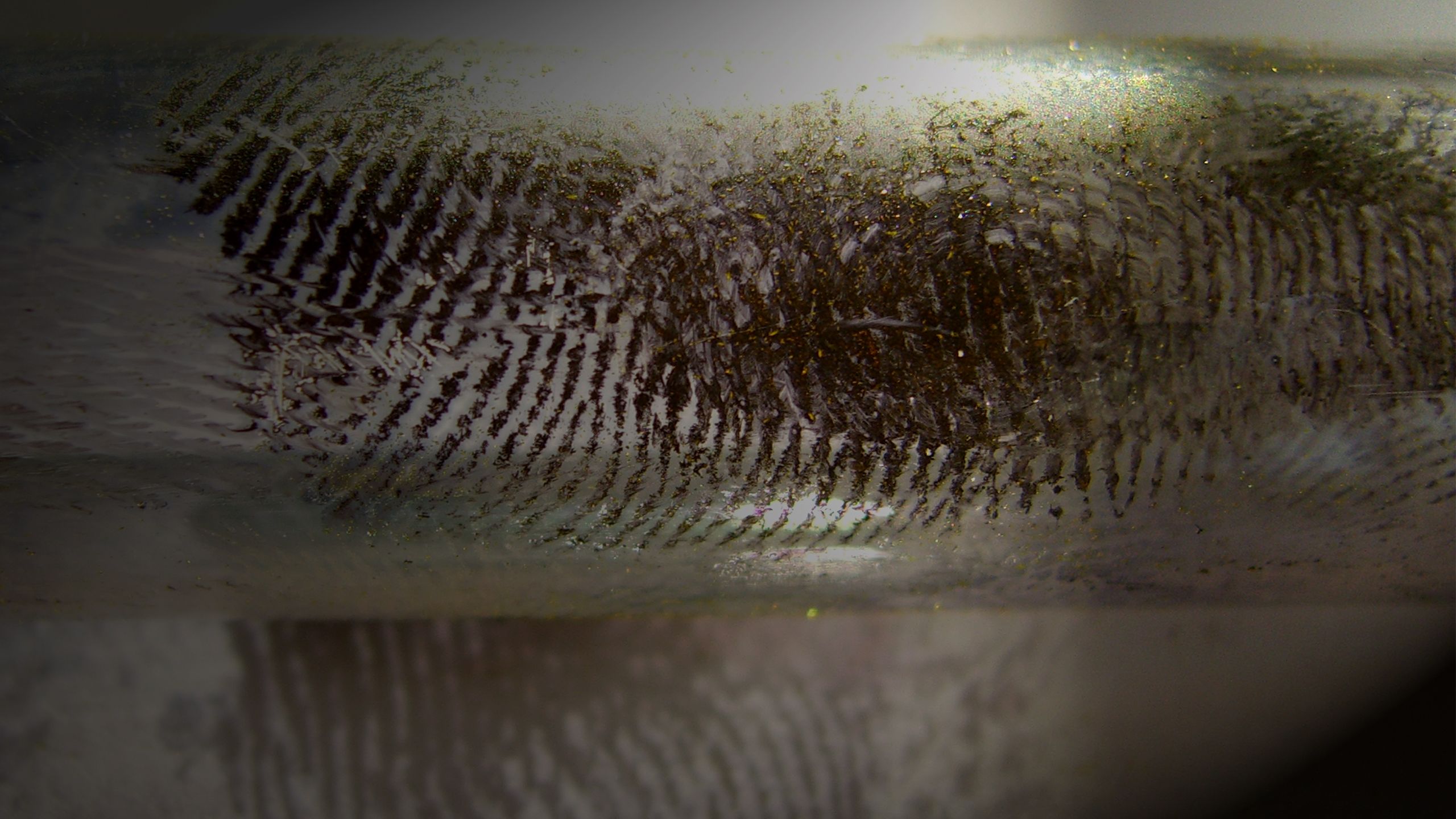

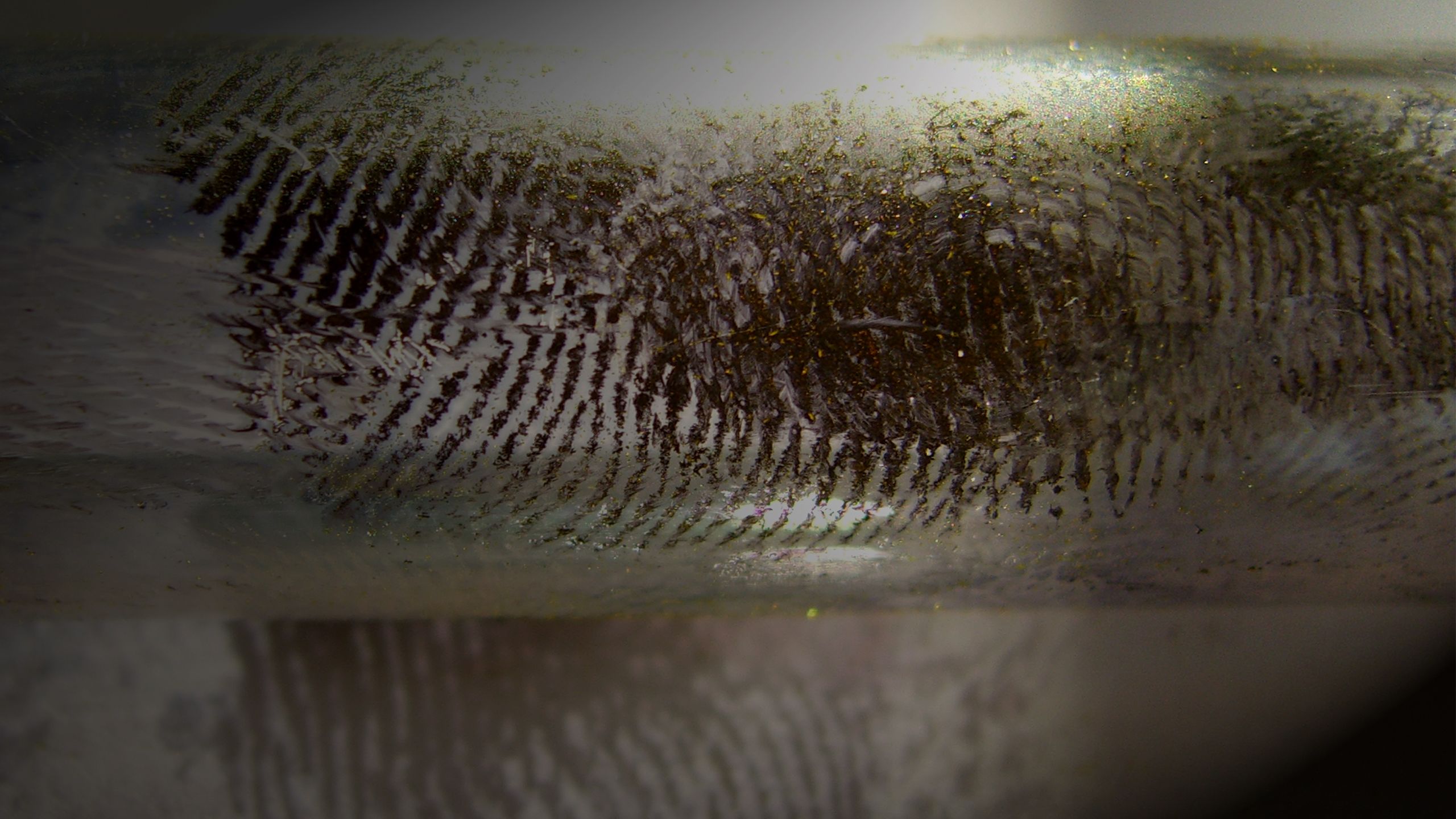

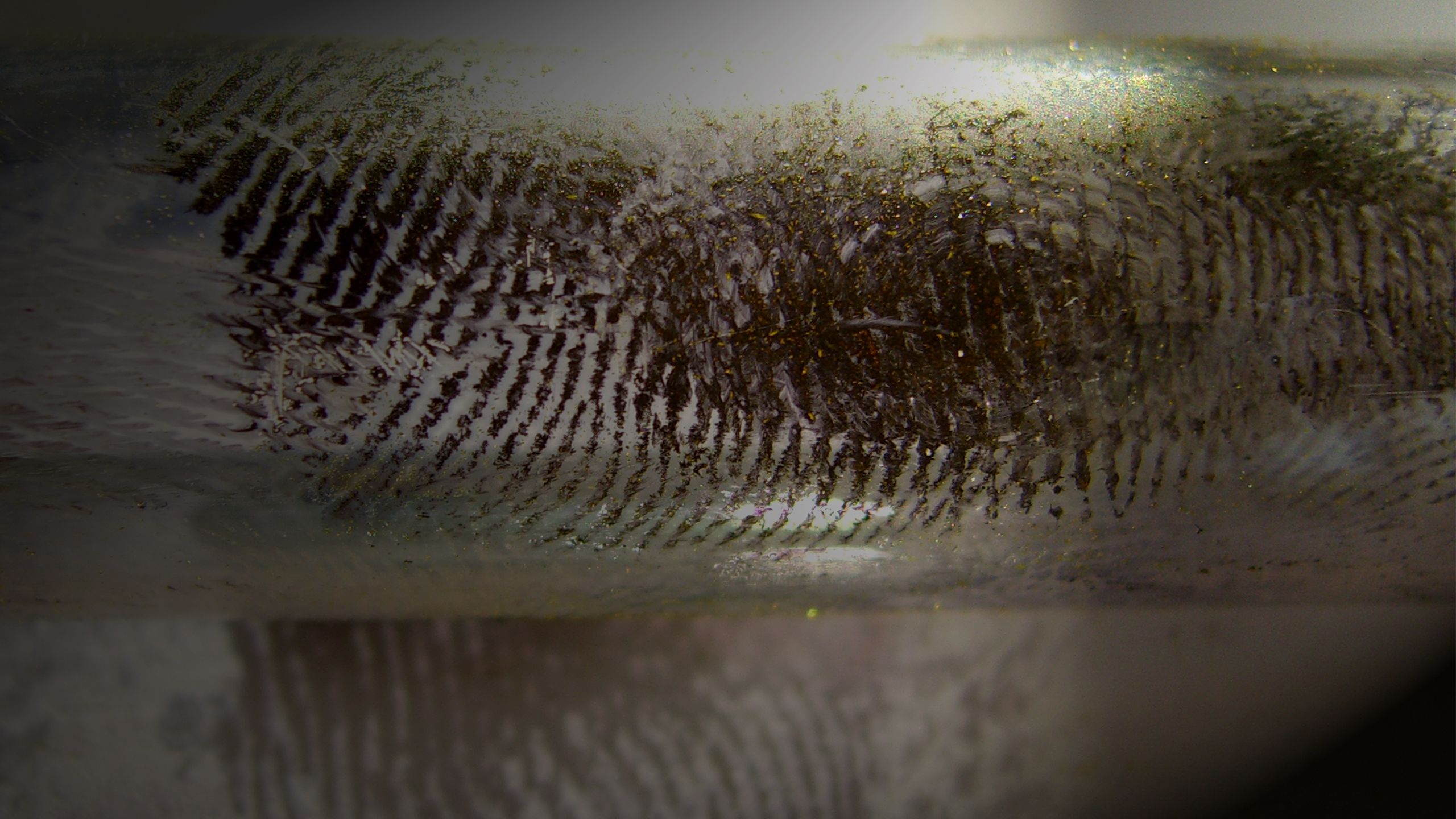

The cutting-edge chemical vapour fuming process provides unrivalled fingerprint development capabilities – including on problematic objects such as ammunition cases and items that have been cleaned.

The device that has been created to house the process is effectively a low-maintenance compact laboratory that semi-automates the science required to produce consistently high-quality fingerprints.

A precursor chemical is heated, and the resulting vapour interacts with surfaces to reveal the latent fingerprints.

The user-friendly software makes the complex chemistry behind the technique a simple one-step process.

'This fingerprint technology will make

it much harder for criminals

to escape justice'.

Former Defence Minister, Harriett Baldwin MP

RECOVERing the impossible

Current fingerprint recovery systems struggle to retrieve usable prints from notoriously difficult surfaces that have been exposed to extreme heat, deformation or cleaning.

RECOVER can. It yields high-quality fingerprints from spent bullet cartridges, IED (improvised explosive device) fragments and items washed clean or submerged for an extended period. Because it is a fuming process, even the minuscule gap between sides of metal that have been folded together can be accessed, revealing prints from the inner surfaces.

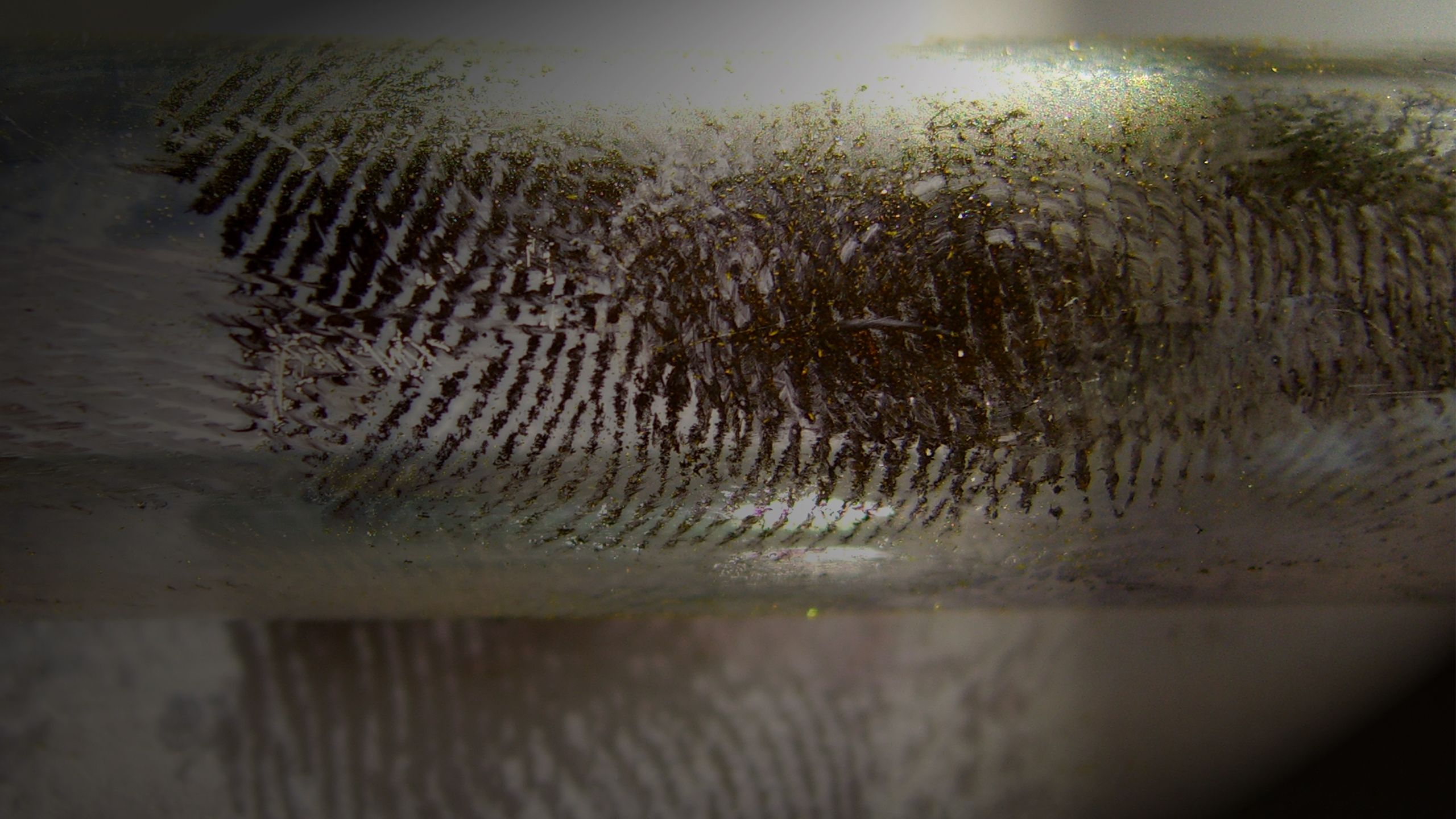

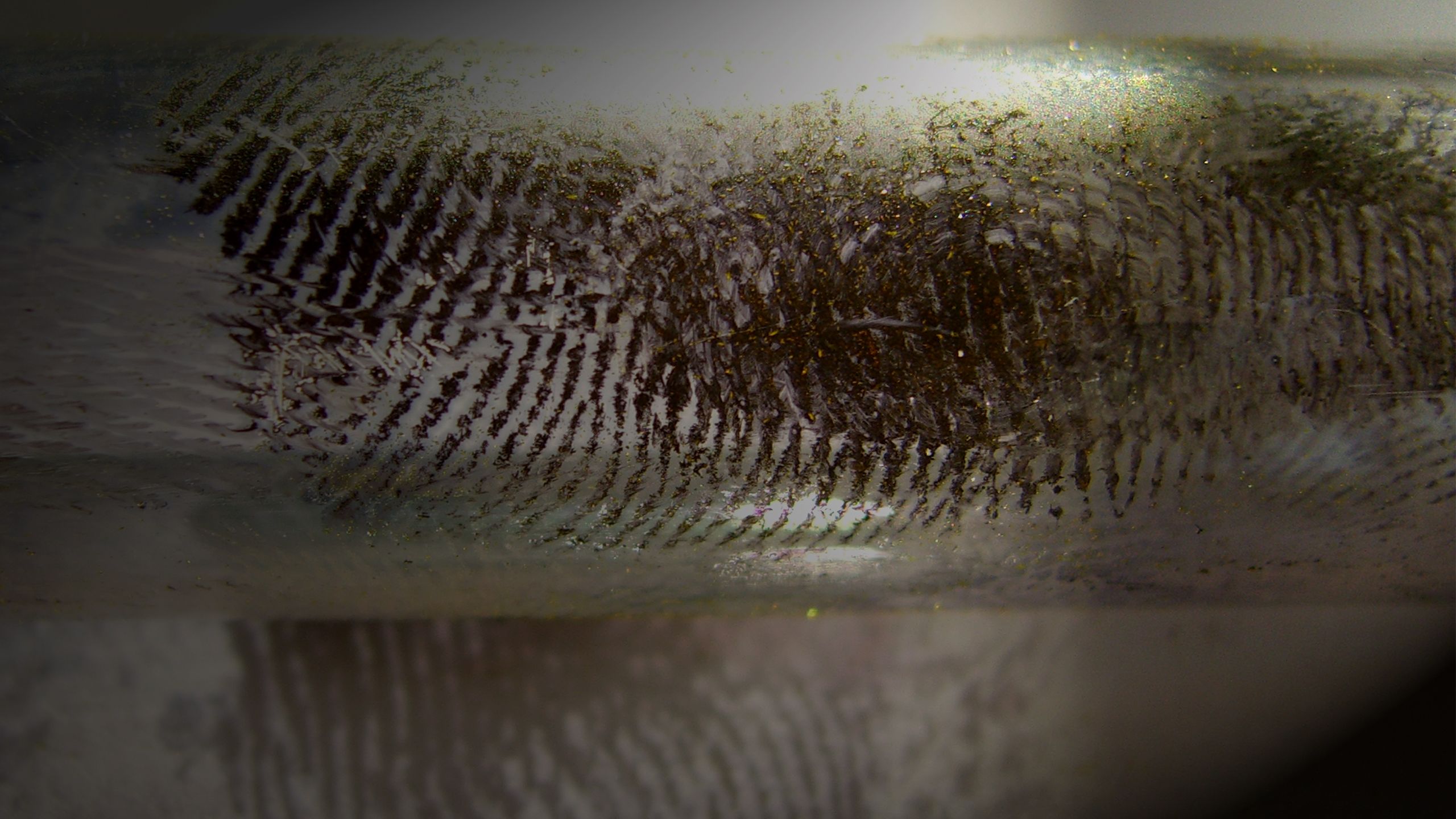

The images drawn from the prints are high resolution, revealing even minute third-level detail, including pores in the skin – significantly enhancing the chance of print-matching and identification.

“All this stemmed from one observation, of one sample vial, with one fingerprint on it.”

Dr Paul Kelly, Reader in Inorganic Chemistry, Loughborough University

A collaborative approach

An effective three-way collaboration – comprising the University, CAST and DSTL – enabled the successful development of this game-changing technology, with each partner bringing unique strengths to the table:

- Loughborough University: the fundamental understanding of the chemistry involved

- DSTL: the operational need and funding to drive the project forward

- CAST: a strong track record for progressing scientific concepts to successful application.

Global forensic manufacturers Foster & Freeman Ltd (F&F) joined the project in 2017, providing the necessary expertise to refine and optimise the technology for the security marketplace.

Then, in late 2018, RECOVER was commercially launched.

“The development of RECOVER shows how important it is with any ground-breaking technology for academic researchers to collaborate with commercial partners. Together, we can transform the initial discovery into something fit for purpose as a useful, potentially lifesaving, commercial entity.”

Dr Roberto King, Research & Development Application Specialist with Foster & Freeman

Fingerprints of the future

Marking a step change in crime detection and security, RECOVER has generated great interest amongst the security sector. F&F have already received orders for the system and some units are in place and will soon be playing their part in genuine forensic investigations.

To continue the close working relationship and knowledge transfer as RECOVER continues to evolve, F&F are establishing laboratories on the University’s Science and Enterprise Park that will produce the chemical reagent used in the RECOVER process.

And it would seem that the technology has hit the market at just the right time. In May this year, the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee warned that forensic science in England and Wales had been plunged crisis – further raising the risk of crime going unsolved.

Dr Paul Kelly says, "That one fingerprint on a sample vial back in 2008 has inspired a whole web of activity across campus, not just involving fingerprints. We have looked at topics as diverse as heritage crime, metal theft and bodily fluid analysis, working a with a range of partners including the Home Office, Historic England and various UK police forces.

"We’re excited to see how RECOVER performs in the field, and the impact it has on law enforcement and security worldwide.”

Photo credits

- Kat Wilcox from Pexels

- Bill Oxford on Unsplash